Feed curiosity, not memory

From my school days to university, I kept circling back to the same uncomfortable question: what does learning better even mean?

Because I didn’t always learn better growing up.

I learned to get good grades.

You don’t always get time to let your curiosity drive. I’d read, get a rough sense of the concepts. Study. Skim. Perform. Forget. Repeat. The machine worked. The grades came. But somewhere along the way, the thing that used to make learning feel alive — curiosity — went quiet.

The Storage Drive Problem

You probably know the feeling. You start learning something new, and the first thing you do is build a checklist. Ten articles, three videos, a course. You’re not chasing a question anymore. You’re filling your head like a storage drive.

That’s information.

It isn’t the same thing as understanding.

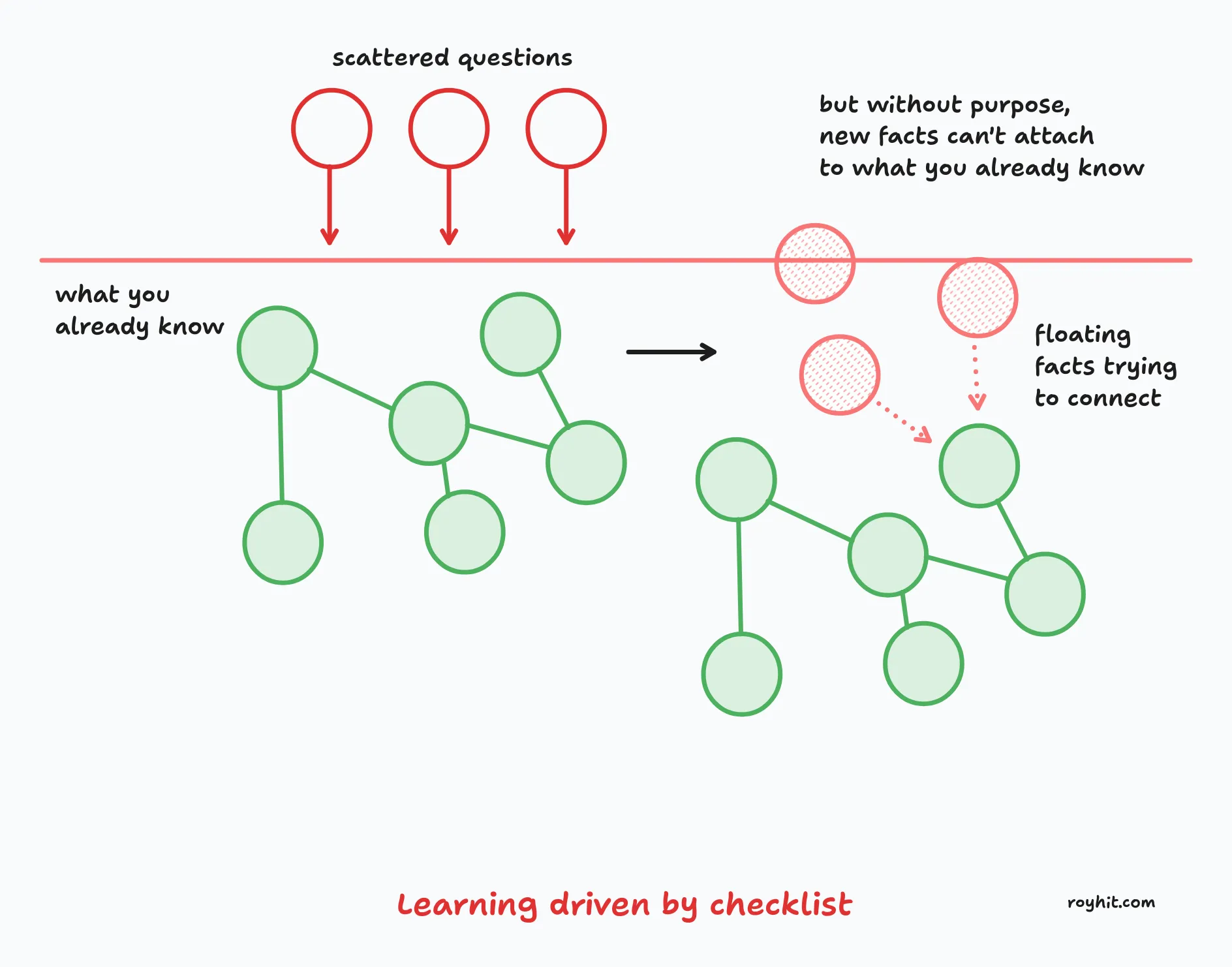

Look at what happens when you approach learning without a guiding question:

You encounter random facts. Questions come from checklist, not curiosity. There’s no anchor point. The ideas are there, but they don’t quite click with what you already know. You try to force connections (that weak dotted line), but nothing sticks. Most of what you encounter remains disconnected. Facts try to connect, but find nowhere to attach.

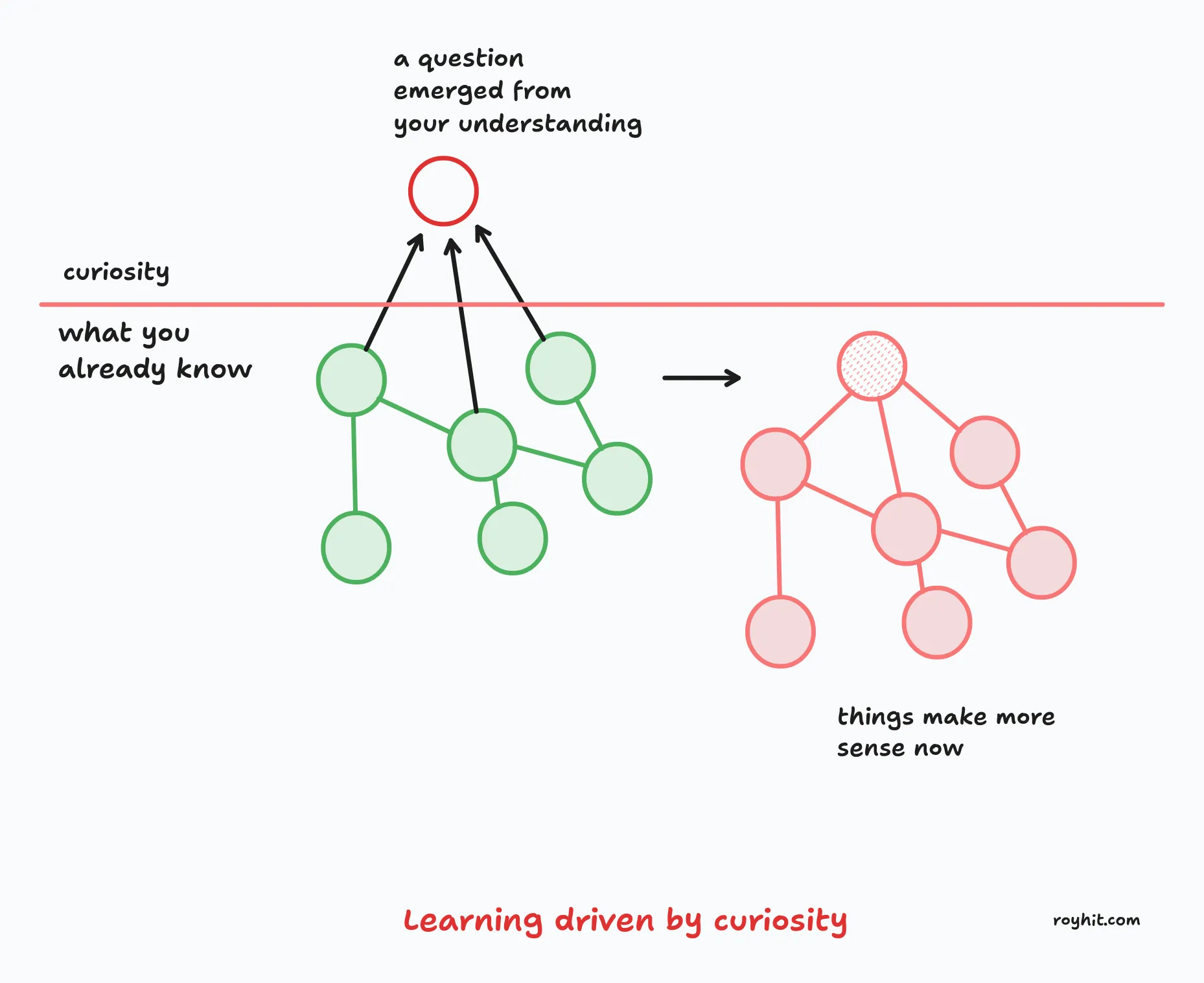

Now let’s look at another approach of learning.

You start from what you already know. A question emerges — something you’re genuinely curious about. That question creates a bridge. New understanding connects naturally to old understanding. The structure grows organically.

The Architecture of Understanding

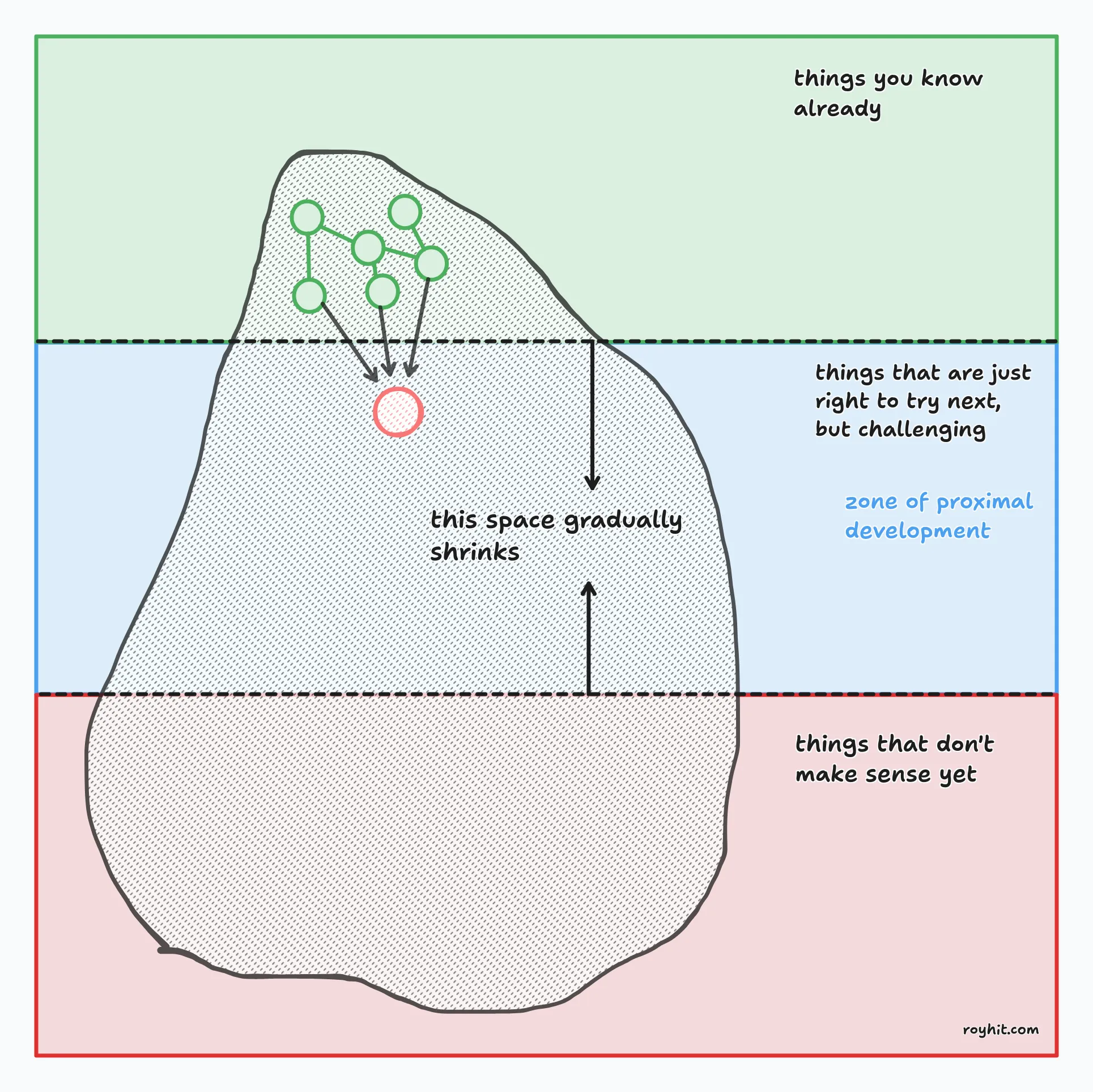

Cognitive science tells us: we only learn well when new ideas attach themselves to old ones.

This isn’t a metaphor. This is literally how knowledge works.

Constructivism — the learning theory pioneered by Piaget and expanded by Vygotsky — tells us that understanding is built, not transferred. You can’t pour knowledge into an empty vessel. Instead, learners construct new understanding by connecting it to what they already know. Piaget called this assimilation (fitting new info into existing schemas) and accommodation (modifying schemas when new info doesn’t quite fit). For example, as a child, when you saw a four-legged animal, you learned it was a dog. That’s new information. Then you learned a four-legged animal could also be a cat. Now you’ve modified your existing knowledge of four-legged animals.

But here’s what the textbooks don’t emphasize enough: you need a reason to build.

That reason is curiosity.

Curiosity does the architectural work for us. It creates a little hook in the mind. A question appears, and suddenly the next piece of knowledge has somewhere to land. And then the next. And the next.

It’s like first-principles thinking, but gentler. You don’t strip everything down to atoms. You just start from what you already understand and ask the next honest question.

“i know velocity changes when something pushes on an object. so why does a rocket accelerate when nothing seems to push on it?”

Now you’re not throwing facts into silence. You’re following a thread.

Why This Matters

The dominant model of education treats learning like data transfer: here’s the curriculum, here’s the material, here’s the test. Learn this, then this, then this. But without curiosity, without genuine questions connecting each piece, you end up with a head full of floating facts that never quite make sense.

Vygotsky introduced the concept of the zone of proximal development — the sweet spot between what you can do alone and what’s completely beyond you. But you only enter that zone when you’re reaching for something. When you have a question pulling you forward.

Learning Better

So what does learning “better” actually mean?

Not faster. Not more efficiently. Not optimized for recall on a test.

Better means feeding curiosity instead of feeding memory.

It means starting with genuine questions — your questions, not someone else’s learning objectives. It means building outward from what you already understand rather than trying to memorize disconnected facts. It means letting understanding grow organically.

So write your questions from curiosity. Explore them. Write what you understand — in your own words. Notice the next question that emerges. Follow it.

References

Fosnot, Catherine Twomey. “Constructivism: a psychological theory of learning.” (1996).