The Hidden Cost of System Calls (And How Buffering Fixes It)

Here we’re reading data from a file or network socket. The code looks simple enough:

InputStream input = socket.getInputStream();

int byte1 = input.read();

int byte2 = input.read();

int byte3 = input.read();But the program is incredibly slow. Not because the algorithm is inefficient, but because of how computers actually read data.

This isn’t specific to Java, Python, or any particular language. It’s a fundamental problem in how programs interact with the operating system. Understanding it makes us better programmers regardless of what language we use.

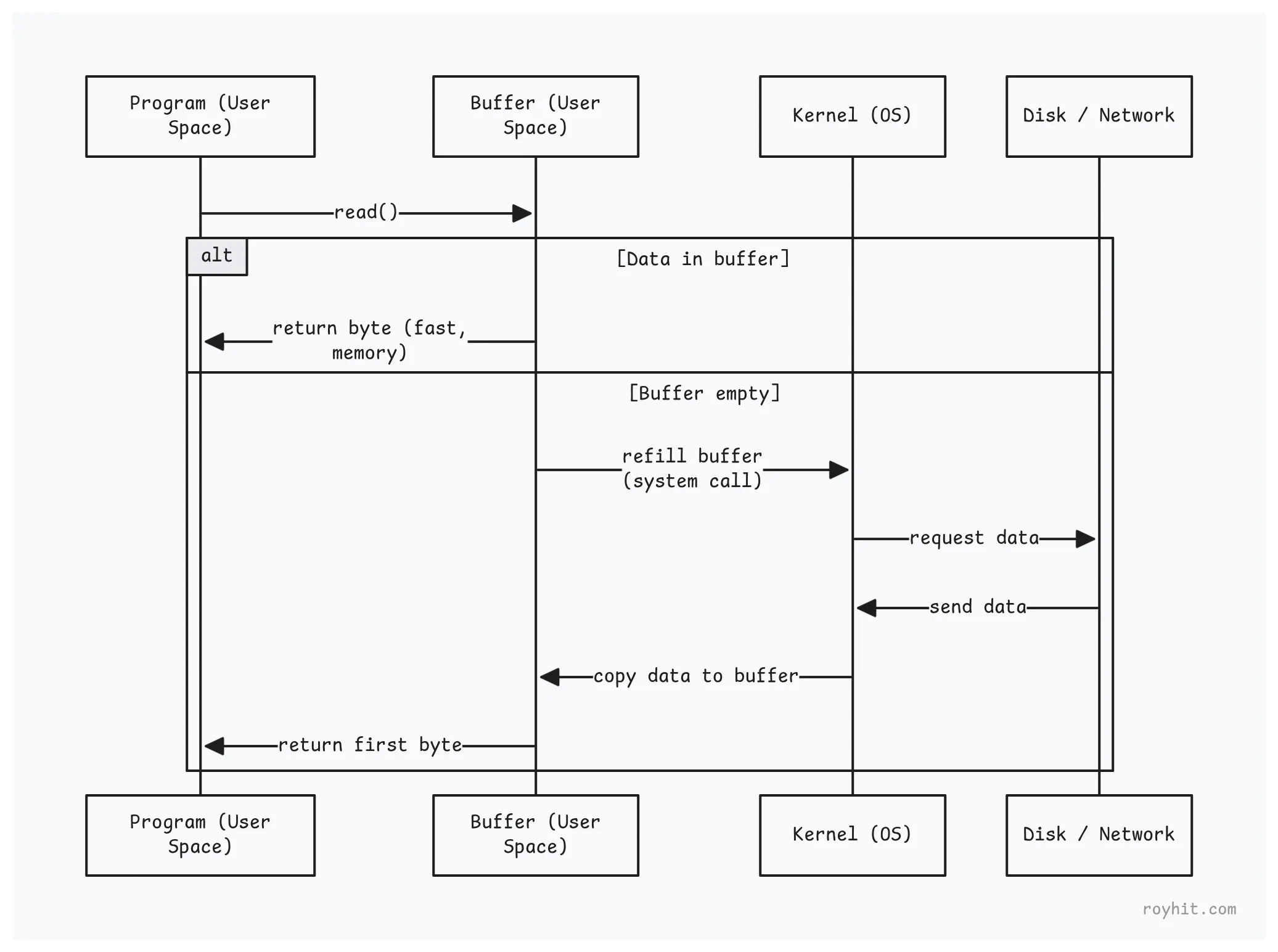

When we call read() to get data from a file or network, we’re not just grabbing bytes from memory. We’re asking the operating system to do work on our behalf, and that work is expensive.

Programs Live in User Space

Applications run in a restricted area of memory called user space. Programs can’t directly touch hardware like disk drives or network cards. The operating system controls all of that, and it runs in a protected area called kernel space.

When we need data from a file or socket, we have to ask the OS for help.

The System Call

Calling read() triggers a system call. This is a special operation that transfers control from our program to the operating system kernel. The CPU has to:

- Save all the program’s current state (registers, instruction pointer, etc.)

- Switch to kernel mode

- Let the OS do its work

- Switch back to user mode

- Restore the program’s state

This context switch takes time. On modern hardware, it’s roughly 1-10 microseconds depending on the CPU and what needs to be saved.

Once in kernel mode, the operating system:

- Checks if the requested data is in its internal buffers

- If not, waits for the disk controller or network card to provide it

- Copies the data from kernel space to the program’s memory

- Returns control back to the program

Another context switch happens to return to our code. Only then do we finally get our byte.

The Cost

To read one byte, we’ve spent roughly 2-20 microseconds just on context switching. Actually accessing a byte from memory takes about 1 nanosecond.

We’re spending 99.99% of our time asking for permission and 0.01% actually getting the data.

Let’s say we want to read “Hello World” character by character. That’s 11 characters. Here’s what happens without buffering:

with open('file.txt', 'r') as f:

for i in range(11):

char = f.read(1)This makes 11 system calls. Each one involves two context switches (entering the kernel, then returning). If each context switch takes 10 microseconds, that’s:

- 11 system calls

- 22 context switches

- ~220 microseconds of overhead

- Just to read 11 bytes

Now imagine reading a 1MB file one byte at a time. That’s 1,048,576 system calls. We’ll spend several seconds just doing context switches.

The Solution: Buffering

The fix is surprisingly simple. Instead of asking the OS for 1 byte at a time, we ask for a large chunk once. Then we keep that chunk in the program’s memory and serve requests from it.

Here’s how it works:

The first time we call read(), the buffering layer makes a system call and reads 8KB of data into an internal array. It returns the first byte to us. The next 8,191 calls just grab bytes from that array in memory. No system calls needed.

When the buffer runs out, it makes another system call to refill. That’s it.

The Implementation

This Pattern Exists in Every Language. Here’s what a buffered reader looks like internally (simplified):

public class BufferedReader {

private char[] buffer = new char[8192]; // 8KB buffer

private int position = 0; // Where we are in the buffer

private int limit = 0; // How much data is in the buffer

public int read() {

// Buffer empty? Refill it

if (position >= limit) {

fillBuffer(); // System call happens here

}

// Return next char from buffer

return buffer[position++];

}

private void fillBuffer() {

// Read up to 8KB from underlying stream

limit = underlyingReader.read(buffer, 0, 8192);

position = 0;

}

}The buffer is just a character array sitting in the program’s heap memory. Reading from it is a simple array access, which is extremely fast.

Why 8KB?

Most languages use a default buffer size around 4-8KB. This number isn’t arbitrary. It balances several concerns:

- A 1MB buffer would waste memory if we’re reading a small file. 8KB is large enough to reduce system calls significantly but small enough to not waste much memory.

- Network data arrives in packets. Ethernet’s maximum transmission unit is around 1,500 bytes. TCP can combine several packets before delivering them to our program. An 8KB buffer typically catches multiple packets in one read.

- Modern CPUs have small, fast caches. L1 cache is typically 32-64KB per core. An 8KB buffer fits entirely in L1 cache, making access extremely fast.

- Modern disks use 4KB sectors. An 8KB buffer aligns nicely with two disk sectors, making disk reads more efficient.

We can adjust buffer size for specific use cases:

// Smaller buffer for memory-constrained environments

BufferedReader small = new BufferedReader(reader, 512);

// Larger buffer for reading huge files sequentially

BufferedReader large = new BufferedReader(reader, 65536);Reading Lines: A Common Pattern

Reading line by line is extremely common in programming. HTTP headers, CSV files, config files, and log files all use line-based formats.

Without buffering, reading lines is painful:

StringBuilder line = new StringBuilder();

while (true) {

int c = input.read(); // System call for each character

if (c == '\n' || c == -1) break;

line.append((char) c);

}Reading a 50-character line makes 50 system calls.

With buffering, readLine() becomes efficient:

public String readLine() {

// Search for newline in current buffer

for (int i = position; i < limit; i++) {

if (buffer[i] == '\n') {

String line = new String(buffer, position, i - position);

position = i + 1;

return line;

}

}

// Newline not found - need more data

fillBuffer();

// Continue searching...

}The method scans through the buffer looking for a newline character. This is a memory operation that takes nanoseconds. Only when the buffer is exhausted does it make another system call.

Reading an HTTP request with 10 header lines might look like this:

BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(

new InputStreamReader(socket.getInputStream())

);

String requestLine = reader.readLine(); // System call, reads 8KB

String header1 = reader.readLine(); // From buffer

String header2 = reader.readLine(); // From buffer

// ... all headers from the same 8KB bufferOne system call reads all the headers at once. The rest of the calls just parse the buffer.

Common Use Cases

Network Programming

Reading from a network socket without buffering is a disaster:

Socket socket = serverSocket.accept();

InputStream input = socket.getInputStream();

// Reading "GET /hello HTTP/1.1\r\n" (20 bytes)

for (int i = 0; i < 20; i++) {

char c = (char) input.read(); // 20 system calls!

}With buffering:

BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(

new InputStreamReader(socket.getInputStream())

);

String requestLine = reader.readLine(); // 1 system callAn HTTP server handling requests without buffering might process 100 requests per second. With buffering, it can handle 10,000+ requests per second.

Log File Processing

# Process a log file line by line

with open('app.log', 'r') as f:

for line in f: # Python buffers this automatically

process(line)Python’s for line in f reads the file in 8KB chunks and splits them into lines in memory. Each line doesn’t trigger a separate system call.

Standard Input

Even reading from the keyboard uses buffering:

while (1) {

char c = getchar(); // Buffered by default

// Process character

}When we type input and press Enter, the entire line is delivered to our program at once. The C standard library’s stdin reads this line into an 8KB buffer. Each call to getchar() returns one character from that buffer. Only when the buffer is exhausted (we’ve read the entire line) does the next getchar() wait for more keyboard input and make another system call.

This is why typing “hello” and pressing Enter doesn’t make 5 separate system calls. It makes one system call to read the line, then serves each character from the buffer.

Thanks for reading!